Editor’s note: This is a guest post by Tonia Christle from Tonia Says for a blog series titled “Growing Up With a Disability.”

As an adult with Cerebral Palsy, I recognize that it isn’t easy to fully immerse ourselves into an experience that we are not living, and it’s a rare opportunity indeed to know how it feels to be a disabled child. So, in this post, I will be revisiting my formative years, sharing memories of things that helped and things that hurt. These are memories that in retrospect are some of the most important aspects when someone is raising a disabled child.

LEARN ABOUT YOUR BABY’S DIAGNOSIS:

Whether you receive a diagnosis for your baby in utero or in early childhood, it’s important to understand that medical professionals are used to fixing and healing. I deeply appreciate them for their abilities but it’s for this same reason that they might give parents a diagnosis for a baby in a grave tone, and even, offer abortion as a first course of action.

Whether your baby has been diagnosed with Cerebral Palsy or something else like Spina Bifida, Down Syndrome or Muscular Dystrophy, realize that there are other resources out there for parents to learn about these things. In addition to learning about medical aspects of your baby’s diagnosis, and seeking out other parents in a similar situation, don’t be afraid to search for information shared by disabled adults who share your baby’s diagnosis. Search for books, blogs and videos created by people in your baby’s community. Listen to what we have to say and realize that our lives are not tragic. In fact, for the most part, we really enjoy them.

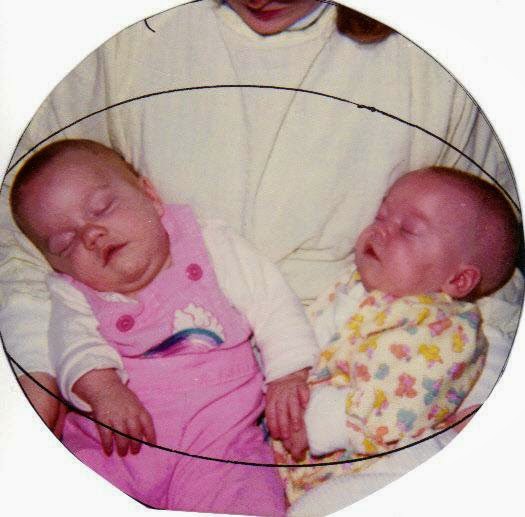

When my mom and grandparents first welcomed my sister and me, they knew nothing about raising disabled babies. According to my grandma, when we were born in the early 1980’s, only a couple of years had elapsed since families institutionalized babies with a diagnosis of CP. Even as late as 1990 when poet and peacemaker Mattie Stepanek was born, his mother was advised to institutionalize Mattie and cautioned not to bond with him. According to Mattie himself, “[The doctors] told my mom…that there was a strong possibility that I would never be able to walk, talk, or think like a ‘normal child.'” [Just Peace p. 18]. Like Mattie’s mom, my mom and grandparents chose to learn about how to look after our medical needs due to premature birth, and when we were diagnosed with CP at eighteen months old, they figured out what we needed and went from there.

BOND WITH YOUR BABY:

Oftentimes, disability goes hand in hand with trauma. Whether that’s a traumatic premature birth or an early diagnosis that parents don’t expect, it isn’t easy to cope. Another thing my family did absolutely right was to bond with my sister and me from the time we were premature babies in the NICU. Though I have no memory of this, I have no doubt that it made a difference in our growth and development.

Making the two-hour drive to visit us each week, and staying as often as possible made a difference to us. We grew to understand – even though we spent months in the hospital – that Mom, or Grandma or Grandpa would be there to hold us and love us regularly.

Mom and Tara (left) visited regularly, even after Tara was released from the hospital

THE IMPORTANCE OF SOCIALIZATION:

Just before starting nursery school at age 2

I’m two years old, at nursery school, and it’s first thing in the morning. Nothing has started and almost no one is here. No other kids. That’s good for me, because I have one objective: I have to get to the Big Bird jack-in-the-box toy, to play with it for a few minutes before school starts. All the other kids tower over me, because I crawl, and they walk. They move faster. If they get here before me, sometimes one of them plays with Big Bird. I don’t know any of those kids. I only know my sister, and I know Big Bird from Sesame Street on TV.

I crawl as fast as I can before any more of them get inside the class with me. I get to the Big Bird jack-in-the-box, which is kept on the lowest shelf – barely off the ground – so I can easily reach it.

It’s hard to play with, because I have to lift one hand off the floor to turn the lever, but I do it. I turn the crank as slowly as possible. I don’t like the popping noise Big Bird makes when he comes out. If I turn it slower, the pop is softer. I like knowing when it’s coming, and I like when it’s softer. It doesn’t make me jump. Now that the jack-in-the-box is open, I love the feeling of having Big Bird right here. I love looking at his plastic self. It’s like he came right out of TV to play with me. I love pushing the green lid down, and watching how Big Bird stays stuck to the inside cover.

The teacher sings the song for circle time, and I look up. The other kids came in, and it’s time to go be with them. I put Big Bird back on the shelf.

He is mine, because I love him the most and I play with him the most. I look around the circle for my sister. We can’t sit by each other because it’s school. The rules are: listen to the teacher, and play with kids we don’t know, not each other.

I miss her.

It’s interesting to me that among my earliest memories is one that demonstrates just how difficult it was for me to connect socially. I wouldn’t say I was unsocialized. I spent most of my life around adult family members. However, the only other child I knew and played with was my identical twin sister, who also has CP. We were the very best of friends and got along well because we each knew our place. As the older twin, she was the boss. As the younger twin, I did what she said. We helped each other out. I spoke for my twin from very early on, when her intense shyness persisted after mine fell away. She helped me reach things and brought me toys.

I was comfortable with my family as they all knew how to move around me. Other children were not only unfamiliar but unpredictable. In nursery school, I remember being fearful and struggling a lot. We played a lot of physical games that didn’t come naturally to me.

I know my parents and grandparents had a kind of tightrope walk to maintain when my sister and I were little, especially having to balance our medical fragility with us having the opportunity to play with other children. Having been born prematurely, I’d been trached as an infant and both myself and my sister were susceptible to respiratory infections. We were hospitalized with pneumonia many times. I don’t fault my family at all for putting our health at the forefront, but I do wish there had been some way to connect with other children as a very little girl.

Today, we have technology at our disposal that my family didn’t have access to simply because it was 1983. Skype and FaceTime are ways for your little one to connect with other children without endangering their health. Even if those are not options for some reason, take an opportunity when we are playing to play with us. Model for us what it looks like to say hello to new friends. Practice introductions and asking if another child would like to play.

This way, perhaps, when we are around children, we won’t struggle knowing what to say or how to begin building a friendship.

ACCEPTING DISABILITY AS A UNIQUE PART OF YOUR CHILD’S IDENTITY:

Age 5, I am posed, hanging onto cabinets behind me

I am five.

My family likes taking pictures of my sister and me. We like being the same. Our clothes match, but not our bodies, because I have a walker and my sister doesn’t. When we get our pictures taken, our family likes us to be the same, too.

They like me to stand without my walker. They say it’s better that way. They are grown-ups, so I listen. I stand leaning against a wall, or hanging onto a chair or a cabinet, or my sister. Just as long as my walker is not in the picture. My walker makes me worse, so I stand far away from it.

I want to look my very best for the picture so I smile, hanging on very tight so I don’t fall.

My family never came right out and said they wanted “normal” kids. However, as a young child, I listened to the way my family spoke about me and my adaptive equipment (which is very much a part of me.) And, though I am now in my thirties, pictures of me with my walker, crutches or wheelchair are rare finds. Many pictures are portrait-style and don’t even include my legs.

I would never encourage any parent to deny their feelings after the traumatic birth or unexpected diagnosis of their child. However, be mindful of how you express those feelings around your child. Keep them between yourself and another close family member or friend. Do your best to speak positively about us (including our adaptive equipment), even if you are sure we won’t remember because we’re young, or that we can’t understand what you’re saying.

We remember. We may not understand all your words and their implications in that moment but we remember how it made us feel. Comments about our differences will stick in our heads long after they leave yours.

We remember. We may not understand all your words and their implications in that moment but we remember how it made us feel. Comments about our differences will stick in our heads long after they leave yours.

Instead, seek out disabled adults. Make friends with us. It will do a world of good for your child’s self esteem to see that their family members want to hang out and talk to people like them. Also, it’s great to have a disabled grown up in their lives to let them know that we are not the only one. Being friends with us will constantly bring to mind that, though they may have to do things differently, that’s okay. Your child is unique and special because they use adaptive equipment. It is something to celebrate, because this equipment allows your child the freedom to live the life they want to live. Practice framing it as such for your little one. It will make such a difference in how they see themselves.

CLOSING THOUGHTS:

If you are a new parent, just starting out on this journey, please don’t feel powerless. You have all the power in the world to impact your baby’s early years positively by learning about their diagnosis through networking with disabled adults, bonding with your baby, socializing your toddler and accepting your kindergartener’s differences as a unique part of their identity.

“…My story is, in many ways, very sad. And angering. And scary. And frustrating. But I don’t live sad, or angry, or scared, or frustrated. Of course I have all of these feelings in my life. But, I choose to do things to help me cope with these difficult feelings so that I can embrace the joy of living each day.” – Mattie J.T. Stepanek [Just Peace, p. 22].

My sister (left) and me, just hanging out, in our preschool years.

My sister (left) and me, just hanging out, in our preschool years.

***

Tonia is a 30-something woman passionate about bridging the gap between disabled adults and parents of disabled children. She is also passionate about seeing a respectful representation of disability in the media. She blogs at Tonia Says, and you can best reach her at Tonia Says on Facebook.

Tonia is a 30-something woman passionate about bridging the gap between disabled adults and parents of disabled children. She is also passionate about seeing a respectful representation of disability in the media. She blogs at Tonia Says, and you can best reach her at Tonia Says on Facebook.

Special Needs Parents, Are You Surviving?

I created a guide with 13 practical ways to help you find peace in the midst of chaos, opt in to make sure you get a copy of this freebie!

Very well written. We need to hear more voices from people with disabilities. There is so much prejudice.

Sandy,

Thank you for reading! I appreciate it!

Beautifully written post, Tonia. I love that you are able to embrace the gifts that your family gave you and appreciate how they fought for you and yet you can evaluate and attempt to break away from some of the unhealthy/damaging aspects of your childhood, such as the overemphasis on being “normal.” As a triplet with CP, I can relate to so much of your post! Like you, I had a family that fought for me and encouraged me to be the best that I can be (and I am so, so grateful for them), and yet I too harbor some of those self-conscious feelings about adaptive equipment and accommodations!

K, I don’t know how I missed this comment previously! I really appreciate that you read this and can relate so specifically. I hope this has you feeling less alone. Thanks so much for reading!